A Visual Language

Shared Understanding

Imagine you’re in a room with several other people. You’re standing in front of a whiteboard attempting to explain a few ways in which information might be presented – for example as a list, or a table of items, or as an individual item with more details. You’ve just started speaking and haven’t drawn anything on the whiteboard yet. After a minute or two you’re not sure if you’re being understood. The other people in the room are looking at you with puzzled expressions. After another minute or so you’re convinced you’re not being understood and discover that each person in the room speaks a different language, and understands very little of the language you’ve been using.

Undeterred, you simplify your speech, begin using your hands, and start drawing simple illustrations on the whiteboard. You draw a table with a simple dataset, and then an arrow from one of the rows in the table to a more detailed view of a single row in the table. You ask each person in the room to follow your example by drawing a simple table and a detailed item view (with much hand gesturing and an enthusiastic expression). You also draw very large labels on top of each view, calling the first a ‘list view’, and the second a ‘details view’. Incredibly, everyone now understands what you’ve been trying to illustrate. For bonus points, you draw a combined list and details view (a classic parent child relationship) place a new label above this and everyone nods in approval. Success.

In reality you’re unlikely to start a meeting without being fairly sure that everyone in the room has at least a basic understanding of the language being used to communicate. However, as soon as you begin discussing more specialized topics or concepts, you may be confronted with the same puzzled expressions and a complete lack of understanding from people with very different backgrounds, or different areas of expertise.

The key then, as hinted at in an earlier post, is to try to establish a common vocabulary - a vocabulary of design patterns that everyone can understand and share.

Build it Together

In our first post we talked about the importance of separating ‘problem statements and goals’ from ‘solution statements’.

Once goals for components of a system are reasonably well defined, we're ready to begin other phases of work, including exploring possible design solutions. Establishing early guidelines and patterns will allow all members of the project team (and ideally representatives from your target audience) to discuss possible solutions. That’s not to say that professional data modelers or designers won’t be needed to help produce more refined designs, but at a certain level - and with a basic shared vocabulary of design patterns to hand, everyone can participate.

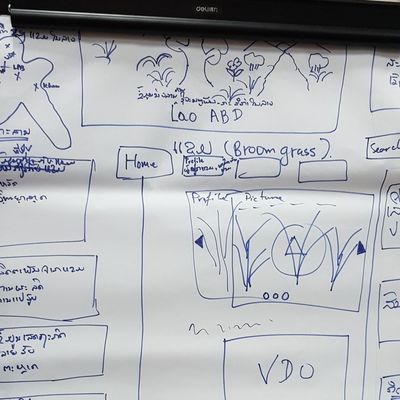

Below is an example paper prototype that a team of subject specialists created after having been given some basic guidelines, templates, and plenty of pens and paper.

Several teams participated in the exercise above - each creating their own paper prototypes, in turn helping to identify common elements and set priorities in design.

Design patterns and language are an incredibly important part of every project. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the greatest cost of a project is not the actual system implementation, but the ‘cost of coordination’ associated with communication, planning, requirements, and design. The use of visual design patterns can help to reduce these costs, while simultaneously giving everyone involved the satisfied feeling of being understood, and making progress.